Quintze Hut

Properly constructed, this poor man’s igloo can be body-heated to above freezing on a 20-below day, higher if you light a candle.

Pole and Bough Lean-to

One of the most ancient shelters, the single wall of a lean-to serves triple duty as windbreak, fire reflector, and overhead shelter.

Open Shelters

Bough structures that reflect a fire’s warmth are the most important shelters to know how to build. They can be erected without tools in an hour provided you are in an area with downed timber-“less if you find a makeshift ridgepole such as a leaning or partly fallen tree to support the boughs.

A-frame

The pitched roof of the A-frame bough shelter offers more protection against the wind than a lean-to and can still be heated by fire at the entrance. One drawback is that the occupant can’t lie down parallel to the fire for even warmth.

Enclosed Shelters

These take more time to build than open shelters (at least three hours), but your efforts will be doubly rewarded. Not only can the shelter be warmed by a small fire, reducing the need to collect a huge pile of wood, but the firelight reflects off the walls, providing cheery illumination for sitting out a long winter night.

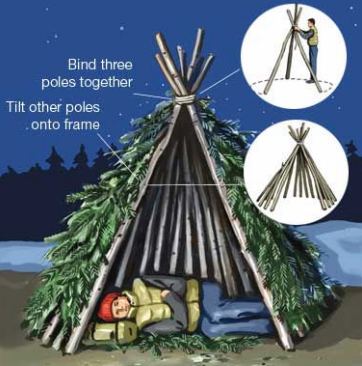

Wigwam

A complex version of the wickiup, this is built with long, limber poles bent into a dome-shaped framework to maximize interior space.

Salish Subterranean Shelter

Used by Pacific tribes from Alaska to present-day California, pit shelters are impractical unless you have a digging implement, but they offer better protection from extreme heat and cold than aboveground shelters.